It’s hard, of course, to compete with a beloved classic, so maybe the best way to read this new book is to forget about The Handmaid’s Tale and enjoy it as an artful feminist thriller. And the more we get to know Agnes, Daisy, and Aunt Lydia, the less convincing they become.

However curious we might be about Gilead and the resistance operating outside that country, what we learn here is that what Atwood left unsaid in the first novel generated more horror and outrage than explicit detail can. This dynamic created an atmosphere of intimacy. That narrator hinted at more than she said Atwood seemed to trust readers to fill in the gaps. The Handmaid’s Tale combined exquisite lyricism with a powerful sense of urgency, as if a thoughtful, perceptive woman was racing against time to give witness to her experience. This approach gives readers insight into different aspects of life inside and outside Gilead, but it also leads to a book that sometimes feels overstuffed. And there's Aunt Lydia, the woman responsible for turning women into Handmaids. There’s Daisy, who learns on her 16th birthday that her whole life has been a lie. There is Agnes Jemima, a girl who rejects the marriage her family arranges for her but still has faith in God and Gilead.

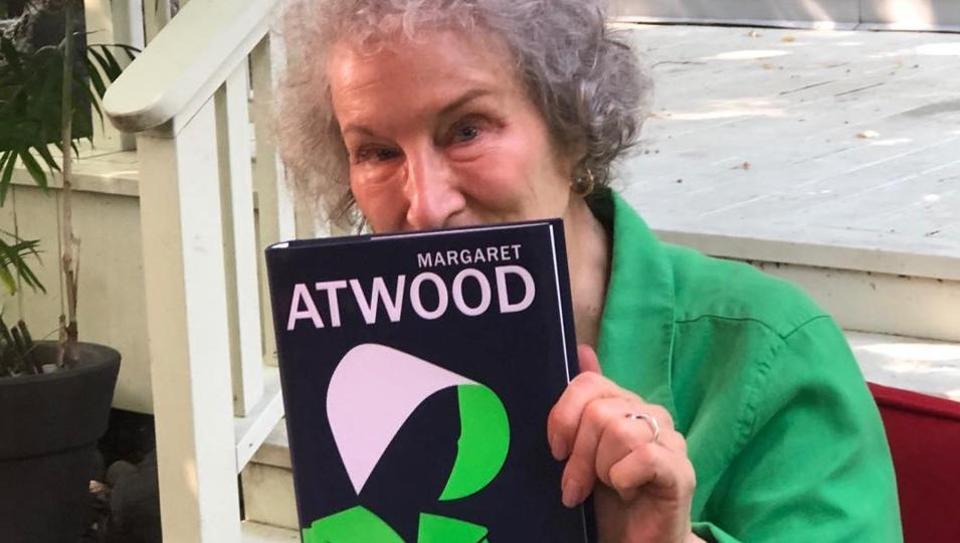

Like the novel that preceded it, this sequel is presented as found documents-first-person accounts of life inside a misogynistic theocracy from three informants. Atwood herself has spoken about how news headlines have made her dystopian fiction seem eerily plausible, and it’s not difficult to imagine her wanting to revisit Gilead as the TV show has sped past where her narrative ended. The Handmaid’s Tale (1985), consistently regarded as a masterpiece of 20th-century literature, has gained new attention in recent years with the success of the Hulu series as well as fresh appreciation from readers who feel like this story has new relevance in America’s current political climate.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)